Preface: The Opioid Crisis

Opioids are used to modulate pain signals. The human body possesses an endogenous opiate pathway; this is how the brain modulates pain internally. The major neurotransmitter of the analgesia system is enkephalin, which inhibits a first-order presynaptic neuron from releasing substance p, and the second-order postsynaptic neuron from depolarizing; thus, preventing the propagation of an impulse from further ascension into a third-order neuron in the thalamus. This effectively halts the pain signal before it can be perceived in the somatosensory cortex. When the endogenous opiate system is activated, enkephalin binds onto receptors of the presynaptic neuron and stimulates a small interneuron in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord’s dorsal horn. The stimulation of this opioid neuron is the step which prompts the release of enkephalin. Opioids also trigger a release of endorphins, the body’s chemical reward system. As the body builds tolerance to opioids, it slows the production of endorphins. As result, higher doses of opioids are needed to achieve the same feelings of pleasure and analgesic effects.

This characteristic of opioids makes them a helpful treatment for acute pain, as well as a poor solution to chronic pain¹. Current treatment options for chronic pain include: opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anticonvulsants, SSRIs, and steroid injection. Most of these approaches aim to decrease neuronal signaling. Overall, there are limited treatments for chronic pain and so it remains that the use of opioids for treatment is unfortunately common. In New Zealand, the number of doses per million has quadrupled between 2003 and 2013.

The prevalence of chronic pain comorbid with a distinct lack of effective, non-addictive solutions has helped feed an ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States – a trend which is slowly spreading to other parts of the world.

The opioid epidemic – more commonly named the ‘”opioid crisis” (DeWeerdt, 2019) – refers to the modern uptake in opioid prescriptions and overdoses. It is a complex medical and systemic issue affecting national health, and economic and social welfare. The United States has seen the largest increases [in opioid prescriptions and overdoses] in recent history. National Institutes of Health (NIH) 2018 data indicates that in the United States, 128 people die each day of an opioid overdose (NIDA, 2020). Death rates from drug overdoses more than tripled between 1999 and 2017, and those associated with opioid overdoses increased nearly sixfold over that same period (DeWeerdt, 2019). As the problem continues to worsen, more researchers have dedicated time and resources to creating better, safer, and more innovative treatments for chronic pain.

Research Strategies Scientists are Exploring to Create Better, Safer Treatments for Pain

Nature offers a myriad of biological models for investigation. One such example is that of conotoxin, a group of neurotoxic peptides² present in the venom of marine cone snails and certain species of spiders and snakes. Thus far, six conotoxins have successfully passed phases one and two of clinical trials and are currently in their phase three trials:

| Peptide | Target |

| ω-MVIIA | Calcium ion channels (N-type) |

| ω- CVID | Calcium ion channels (N-type) |

| Conantokin-G | NMDAR (NR2β) |

| Contulakin-G | Neurotensin receptor |

| α-Vc1, 1 | nAChR (α9 α10) |

| χ-MrIA | Norepinephrine transporter |

Conotoxins operate by blocking nerve conduction, thereby stopping the propagation of an action potential along a myelinated axon before it reaches the thalamus. All conotoxins possess targets which modulate neuron excitability.

Another example is unique lipids, such as DHEA (synaptamide) found in fish oil. DHEA and PEA are sometimes marketed as ingredients in anti-inflammatory medication. Previously, it was believed that DHEA acted similarly to endogenous cannabinoids by weakly binding to CB1 and CB2 receptors and demonstrating partial efficacy (Paton, Shirazi, Vyssotski & Kivell, 2020). The first portion of the hypothesis involved proving that DHEA elicited analgesic effects – which was true; DHEA showed cellular effects in attenuating information for a lot less inflammatory cell presence in tissue treated with DHEA, proving it has anti-inflammatory effects in a culture dish, as well as in-vivo (Kivell and Atigari, 2020). The second portion of the hypothesis aimed to prove that DHEA worked through the cannabinoid receptor. However anti-inflammatory effects remained in the presence of CB1 and CB2 receptor inhibitors, thus proving that DHEA does not act through the cannabinoid system. The channel by which DHEA modulates pain is still an ongoing investigation.

In addition to seeking out better drug targets, there is also much research being done towards improving drugs for existing targets; ideally, to create a drug which can be used for the treatment of both acute and chronic pain. The current hypothesis is that of biased agonism: If a drug is G-protein selective, then it will have the positive analgesic effects without the unwanted tolerance effects and respiratory depression associated with activating downstream signaling pathways with β-arrestin. A compound with no signaling bias has a value of 1. When the compound is bias towards the G-protein, its value is less than 1. When the compound is bias towards β-arrestin, its value will be greater than 1. Based on the hypothesis of biased agonism, researchers have been investigating G-protein biased agonists to create an effective analgesic without the unwanted side effects.

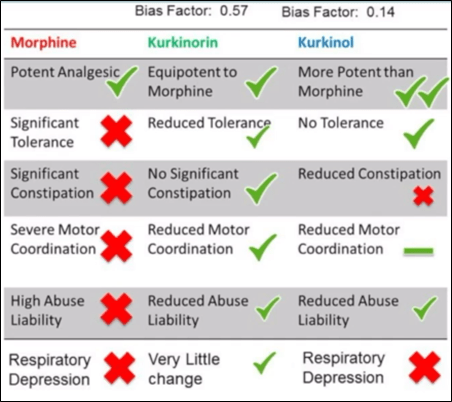

Research involving Salvinorin A (Sal A)³ is an example of a novel µ-opioid antagonist aimed at improving existing targets. Sal A has a special structure that allows it to bind to the κ-opioid receptor. Hence the goal of some research was to synthesize a compound which activates the µ-receptor from Sal A’s structural scaffold (Morani, Schenk, Prisinzano, & Kivell, 2012). The result was a new chemical compound named herkinorin. Herkinorin successfully activates both µ and κ receptors, but does not cross the blood brain barrier. Thus, herkinorin is ineffective as a pain medication due to its inability to reach the central nervous system. And so, researchers developed kurkinorin and kurkinol: two compounds able to permeate the blood brain barrier. Both kurkinorin and kurkinol are extremely potent and much more selective to the µ-receptor than the κ-receptor. They also possess different bias properties: kurkinorin = 0.57, kurkinol = 0.14. In theory, this makes kurkinol more bias to G-protein selection.

In application on in-vivo specimens [mice], the dose response curve4 showed that morphine and kurkinorin are similar in their immediate analgesic effect. Because the interest was in chronic pain medications, the testing was repeated every day until day nine. On day nine, the dose-response curve showed morphine had a more significant shift to the right than kurkinorin. This indicates that morphine had a more pronounced tolerance effect than kurkinorin. In a dose response curve comparing morphine and kurkinol, kurkinol is to the left of morphine and therefore, much more potent. Interestingly, kurkinol’s shift to the right after nine days is not significant, meaning that kurkinol does not show a tolerance effect. Further in-vivo testing of these compounds focused on testing chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain5. Researchers induced four doses of a chemotherapy drug, and tested response to mechanical and cold allodynia6 at day fifteen. Tolerance remains showed that kurkinol was more effective for longer, but still built up a tolerance after 36 days. Kurkinorin and kurkinol both have reduced abuse potential. Kurkinorin also reduces the inhibition of gut motility, however kurkinol does not. Testing the tidal volume of animal respiration, showed there was an observed depression of respiration with kurkinol and morphine, but significantly less-so with kurkinorin.7 The results of this experiment serve to place the biased antagonism hypothesis in question because although kurkinol was less bias to the β-arrestin receptor, it was not the safest [Figure 1] (Kivell and Atigari, 2020).

In conclusion, more research would need to be done to further investigate the side effects of κ-agonists to see if it they are a viable clinical treatment for chronic pain. Like any prospective commercially available drug, kurkinorin also needs to successfully pass three phases of clinical trials to reach the market (extremely rigorous process which usually takes between 5-10 years).

There is ample research taking place to provide better and safer solutions to chronic pain than opioids currently offer – these have only been a handful of examples. Research is taking place both in the form of exploring new targets (such as with conotoxins, DHEA, etc.) and by improving existing targets (as with herkinorin, kurkinol, kurkinorin, etc.).

Footnotes

¹ Acute pain is protective; the perception of pain serves to prevent further damage to the site of injury. Chronic pain lasts longer than the body’s recovery period (typically three months) and serves no physiological benefit. Chronic pain can stem from several sources, including: shingles, phantom limb pain, diabetic neuropathy, stoke, multiple sclerosis, cancer, chemotherapy, etc. One in five New Zealanders (approx. 700,000 individuals) suffer from chronic pain.

² A peptide is a short chain of amino acids.

³ Salvinorin A (Sal A) is a chemical substance purified from the salvia divinorum plant of the sage family.

4 The dose-response curve models the potency and efficacy of an analgesic drug.

5 Chemotherapy causes damage to the peripheral nerve endings via myelin degradation. This degradation often leads to chronic pain for chemotherapy patients.

6 Allodynia is an increased sensitivity to pressure and temperature (particularly cold) from non-noxious sources.

7 Respiratory depression is the fatal consequence of taking opioid drugs.

References

Alder, Kivell & Atigari, 2020

Alder, A., Kivell, B. M. & Atigari, D. (2020). SCIE204 Neuroscience 2020 Pain: Lesson Material. Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved from Victoria University of Wellington.

DeWeerdt, 2019

DeWeerdt, S. (2019). The natural history of an epidemic. Nature. Springer Nature S10, vol 57. Retrieved from Nature.

Kivell and Atigari, 2020

Kivell, B. M. & Atigari, D. (2020). SCIE204 Neuroscience 2020 Pain: Lesson Material. Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved from Victoria University of Wellington.

Morani, Schenk, Prisinzano & Kivell, 2012

Morani, A. S., Schenk, S., Prisinzano, T. E., & Kivell, B. M. (2012). A single injection of a novel κ opioid receptor agonist salvinorin A attenuates the expression of cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in rats. Behavioural pharmacology, 23(2), 162–170. Retrieved from Google Scholar.

NIDA, 2020

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). National Institutes of Health (NIH). Retrieved from National Institutes of Health.

Paton, Shirazi, Vyssotski & Kivell, 2020

Paton, K., Shirazi, R., Vyssotski, M. & Kivell, B. M. (2020). N-Docosahexaenoyl ethanolamine (Synaptamide) has antinociceptive effects in male mice. European journal of pain (London, England). Retrieved from Google Scholar.