Is a ‘Predator Free NZ’ within reach?

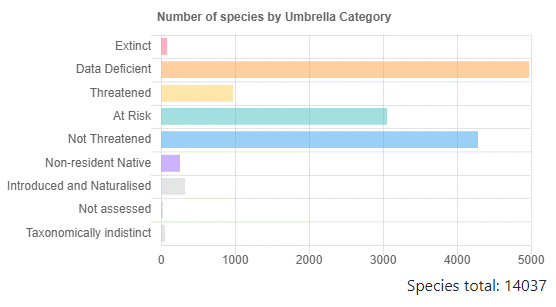

Attaining ‘predator free’ mainland islands in New Zealand is an aspiration that seems increasingly technically viable and predominantly cross-culturally desired. In the context of Predator Free New Zealand 2050, predator free refers to the absence of five introduced species: rats, weasels, stoats, ferrets, and possums. The eradication of these species from select islands has proved an effective method for restoring some of New Zealand’s threatened and at risk native populations, of which – as at July 2020 – there are 967 and 3062, respectively (NZTCS, 2020); although, this list continues to grow as more species are assessed (Figure 1).

Technical Viability

International research across eight countries has informed that 596 native populations have benefitted from the removal of invasive mammals, of which half were in New Zealand (Jones et al., 2016). By extension, this research supports that New Zealand is one of the global leaders in island conservation. Thus, science has proven: (1) eliminating select invasive predators is effective, and (2) New Zealand excels at the practice of producing predator free territories for conservation purposes.

Regular government funding is provided to several non-government organizations and charitable companies which conduct efforts that cumulatively help New Zealand attain predator free mainland. One such beneficiary is Predator Free 2050 Limited which boasts $76M allocated to 12 projects over the next four years. Three of their example projects are: (1) the removal of possums and suppression of mustelids, rats, and feral cats to low levels along 28,500ha of the Banks Peninsula, (2) possum eradication across 9,000ha and predator suppression across 60,000ha in Whangārei, allowing for the recovery of threatened species of native flora and fauna, and (3) possum eradication and predator suppression across 4,700ha around Whākatane while creating jobs and building iwi capacity. Numerous smaller organizations and communities rally around the leadership (and funding) from large-scale charitable organizations like Predator Free 2050 Ltd. Having these types of organizations is integral to the wider predator free movement and for the orchestration of bodies that push to achieve outcomes aligning with predator free timeline and goals.

Some ongoing technical speculations involve finding the most ethical and humane methods of eradicating these invasive species. As a continuation of the example, Predator Free 2050 Ltd. possesses projects which build on well-established trapping schemes, but there is much research taking place on species-specific poisons and the use of genetic engineering (CRISPR technology) to make offspring of select invasive mammals infertile. Pursuing infertile offspring is likely favored as the most ‘humane’ option, though public opinion is relatively polarized on catching, germline editing, and rereleasing animals due to the uncertainty of its consequences. Further research is necessary to our understanding of the best approaches to invasive mammal eradication, but it is widely believed that a combination of these solutions (and population suppression) will all be needed to realize Predator Free NZ 2050.

Culture and Community

There has been some opposition to Predator Free New Zealand 2050 and while most of this discourse has centered around how to eradicate the invasive predators humanely, there are those who disagree with the movement entirely. Dr Jamie Steer, for example, is someone who has worked and studied in the environmental service industry for ~20 years. He has become increasingly well-known for his opposition to Predator Free NZ 2050. His most forthcoming argument is that the best outcome for New Zealand ecology would be to encourage existing species’ adaption to their rapidly changing environments, leaving those which cannot adapt “in the past” (Steer, 2017). This argument is poor, and there is much to be said about this view as it relates to upholding our core values as a treaty island nation. Steer’s argument aligns with a matter-of-fact, Darwinian perspective on the issue: that we must cauterize our conservation efforts on many more species and let nature run its course on those which have been affected. But this perspective is eerily imperialistic and in direct conflict with tikanga Māori values, particularly kaitiakitanga – seeing the land as a body that inherently requires the guardianship and protection. In the most literal sense, one cannot protect the land nor its creatures without preserving it; this is the role of conservation in our environment and sociopolitical ecosystem.

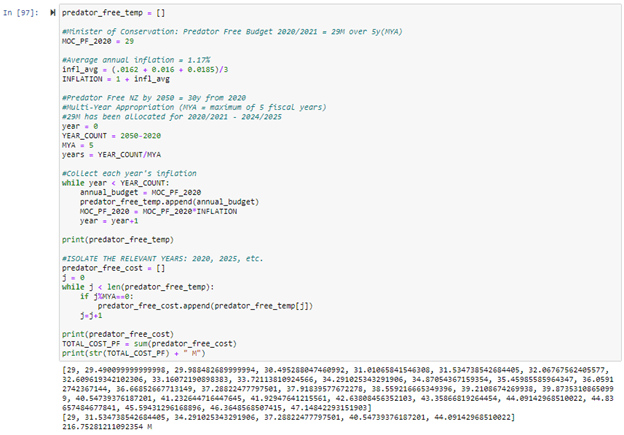

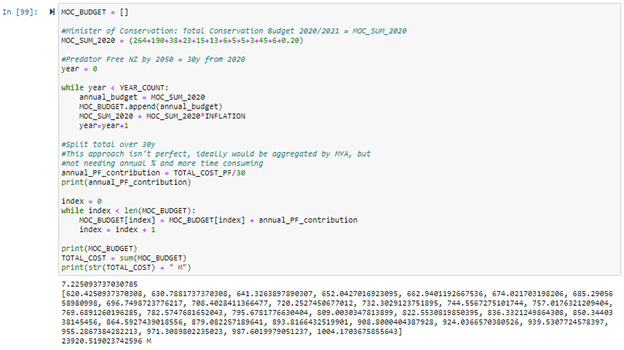

The New Zealand government recognizes its responsibility to honor the values of treaty partners, and uphold its environmental obligations. Recently, there has been an allocation of a $29M multi-year appropriation from 2020/2021 – 2024/2025 towards funding a predator free New Zealand by 2050 (NZ Treasury, 2020).

Using the 2020/2021 environment sector estimates as a forecast of future funding allocations, this amounts to a further projected cost of $216M by 2050. While this sounds like an impressively large number, it is actually just under 1% of the sector’s aggregated funding for the next 30 years. That is to say: $216M is just under 1% of the sum of all allocations to be made by the Minister of Conservation within the years 2020-2050, if we account for inflation and hold constant the current proportion of Vote Conservation (2020/2021) funding allocations (Appendix A).

The average annual costs of Predator Free initiatives and operations has been omitted for time’s sake, but I will close with this: The government has recognized Predator Free NZ 2050 as an ambitious, though attainable, goal and is taking steps to ensure that we are able to reach it. There are major NGO players backing the movement, as well; and research supports that our (New Zealand’s) conservation efforts are among the best in the world. So long as public attitudes do not drastically change over time, the outlook for this movement is quite bright.

Appendix (Mathematical Workings, Python)